Who Were the Canaanites, the ancient Biblical people credited with inventing the alphabet?

The Canaanites were made up of different ethnic groups who lived in the ancient Land of Canaan, and they likely invented the world's first alphabet.

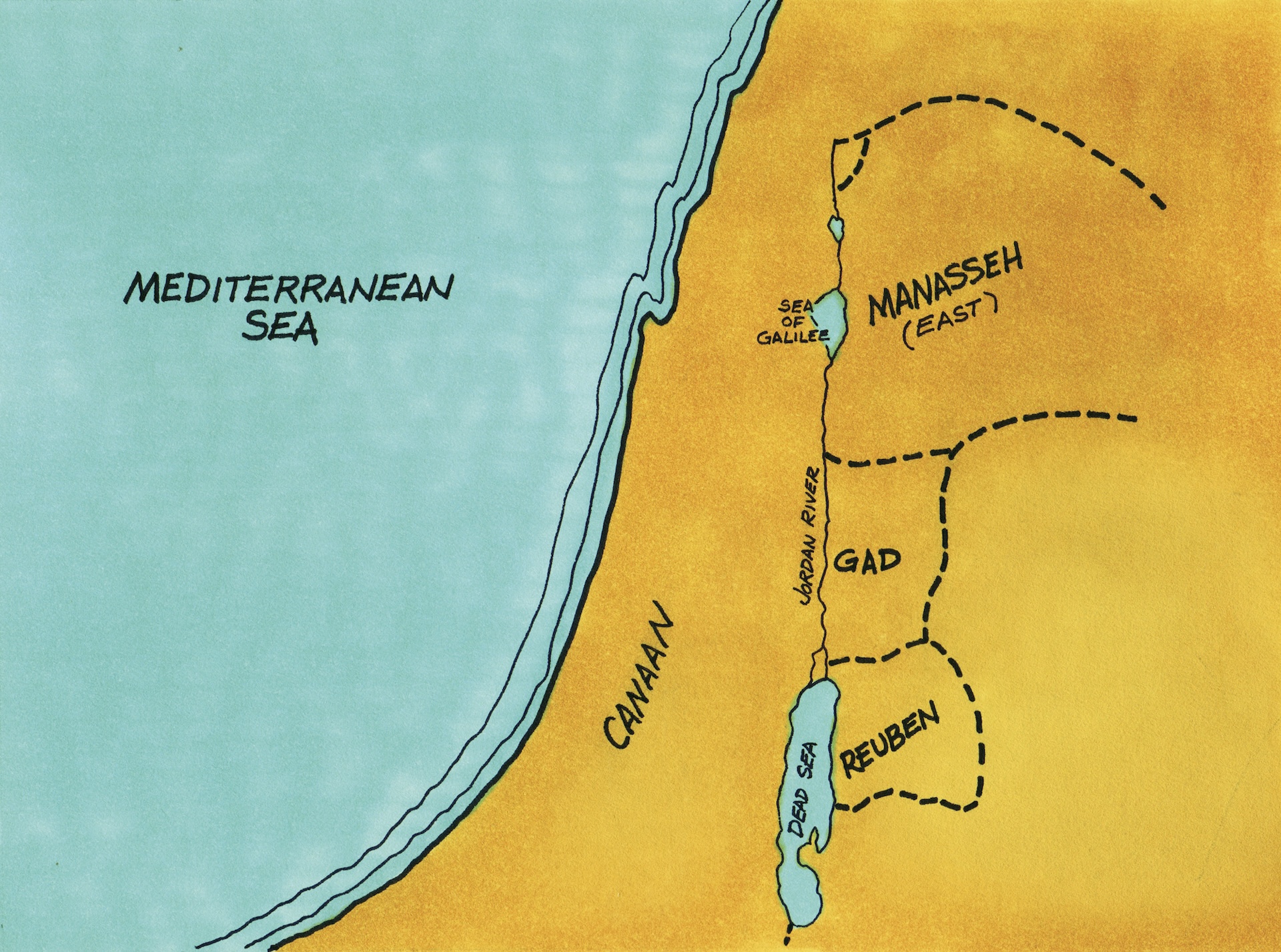

The Canaanites were people who lived in the land of Canaan, an area that ancient texts indicate may have included parts of modern-day Israel, Palestine, Lebanon, Syria and Jordan.

Much of what scholars know about the Canaanites comes from records left by the people they interacted with. Some of the most detailed surviving records come from the site of Amarna, in Egypt, and from the Hebrew Bible. Additional information comes from excavations of archaeological sites that the Canaanites are thought to have lived in.

Scholars doubt that the Canaanites were ever politically united into a single kingdom. Archaeological excavations indicate that the Canaanites were actually made up of different ethnic groups. During the Late Bronze Age (1550 to 1200 B.C.), "Canaan was not made up of a single 'ethnic' group but consisted of a population whose diversity may be hinted at by the great variety of burial customs and cultic structures" wrote Ann Killebrew, an archaeology professor at Penn State, in her book "Biblical Peoples and Ethnicity: An Archaeological Study of Egyptians, Canaanites, Philistines, And Early Israel 1300-1100 B.C.E." (Society of Biblical Literature, 2005).

Genetic findings

Recent DNA research has found that the Canaanites were the descendants of Stone Age settlers in Lebanon; the Canaanites are also the ancestors of modern-day Lebanese people.

In a 2017 study in the American Journal of Human Genetics, researchers looked at the ancient DNA of five Canaanites who lived between 3,650 and 3,750 years ago and who were buried in Sidon, an ancient city in what is now Lebanon. The team compared this DNA with that of 99 modern Lebanese people and more than 300 other people in an ancient DNA database.

The results showed that the Canaanites descended from Stone Age people who had mixed with newcomers from Iran around 4,000 to 5,000 years ago. The study also showed that today's Lebanese are largely Canaanite, although around 3,000 years ago their ancestors mixed with Eastern hunter-gatherers and Eurasian Steppe people.

Ancient records

The earliest undisputed mention of the Canaanites comes from fragments of a letter found at the site of Mari, a city located in modern-day Syria. Dating back about 3,800 years, the letter is addressed to "Yasmah-Adad," a king of Mari, and says that "thieves and Canaanites" are in a town called "Rahisum." The surviving portion of the letter alludes to a conflict or disorder that is taking place in the town.

Another early text that talks of the people who lived in Canaan dates back about 3,500 years and was written on a statue of Idrimi, a king who ruled a city named "Alalakh" in modern-day Turkey. Idrimi says that at one point he was forced to flee to a city in "Canaan" called "Amiya" — possibly located in modern-day Lebanon. Idrimi doesn't call the people at Amiya "Caananites" but instead names a variety of different lands they are from, such as "Halab," "Nihi," "Amae" and "Mukish." Idrimi claims that he was able to rally support at Amiya and become king of Alalakh.

However, this doesn't mean that the different people in Canaan never grouped together. Administrative texts found at Alalakh, and at another city named Ugarit (located in modern-day Syria) show that "the designation 'the land of Canaan' was employed to specify the identity of an individual or group of individuals in the same way that others were defined by their city or land of origin," wrote Brendon Benz, an associate professor of history at William Jewell College in Missouri, in his book "The Land Before the Kingdom of Israel: A History of the Southern Levant and the People who Populated It" (Eisenbrauns, 2016). For instance a male from a city in Canaan who was living at Alalakh or Ugarit could be identified in records as being a "man of Canaan" or being a "son of Canaan," Benz wrote.

A number of texts that mention Canaan come from the site of Amarna, in Egypt. Amarna was constructed as the capital of Egypt by the pharaoh Akhenaten (reign circa 1353 to 1335 B.C), the father of King Tutankhamun and a ruler who tried to focus Egypt's polytheistic religion around the worship of the "Aten," the sun disk. The texts consist of diplomatic correspondence between Akhenaten (and his immediate predecessors and successors) and various rulers in the Middle East. Modern-day scholars often call these texts the "Amarna letters."

The letters show that there were several kings in Canaan. A diplomatic passport written by Tusratta, a king of Mittani (a kingdom located in northern Syria) tells the "kings of the land of Canaan" to let his messenger "Akiya" pass through safely to Egypt, and warns the kings of Canaan that "no one is to detain him."

The letters also show that Egypt held considerable power over these Canaanite kings. One letter, written by a king of Babylon named "Burra-Buriyas," complains about the killing of Babylonian merchants in Canaan and reminds Egypt's pharaoh that "the land of Canaan is your land and its kings are your servants." (Translation from Brandon Benz's book "The Land Before the Kingdom of Israel.")

Egyptian texts also show that Egypt's pharaohs sent military expeditions into Canaan. A stele erected by a pharaoh named Merneptah (reign circa 1213 to 1203 B.C.) claimed that "Canaan has been plundered into every sort of woe." The same stele also claims that Merneptah "laid waste" to "Israel."

Hebrew Bible

The Canaanites are frequently mentioned in the Hebrew Bible. Canaan is described as Noah's grandson; Cannan's father, Ham, saw Noah naked and then told Noah's other sons about it. Enraged, Noah curses Canaan (Genesis 9:24 to 9:25).

The Bible later describes how Noah's descendant Abraham and his wife Sarah journeyed to Canaan, and how the Israelites later left Canaan for Egypt. The Bible details that after the Egyptians enslaved the Israelites, God promised to give the land of the Canaanites (along with land belonging to several other groups) to the Israelites after the Exodus, when they escaped from Egypt.

Once in Canaan, the Israelites fought a series of wars against the Canaanites (and other groups), which led to the Israelites taking over most of the Canaanites' land, according to the Bible. The texts say that the Canaanites who survived had to do forced labor (Judges 1:28). The stories also say that this conquered land was incorporated into a powerful Israelite kingdom that eventually split in two.

The historical accuracy of some of these stories, however, is debated. Some researchers believe that there was no exodus from Egypt, arguing that there's no evidence the Israelites left Canaan during the second millennium B.C.

Canaanite archaeology today

Archaeologists continue to find artifacts from the Canaanites. For example, a team found a 3,000-year-old temple, built by the Canaanites, in what is now southern Israel. Within the temple's inner sanctuary, archaeologists found an idol of the Canaanite god Baal that was the object of prayer and sacrifice. In another excavation, archaeologists in Israel unearthed a 3,800-year-old Canaanite arch made out of mud bricks that may have been used by a cult during the Middle Bronze Age.

Another find in Israel revealed one of the oldest known sentences on record: a plea against contracting lice that was engraved on a Bronze Age comb in the language of the Canaanites. The engraving on the ivory comb translates to "May this tusk root out the lice of the hair and the beard."

Many experts think that around 4,000 years ago, the Canaanites invented the world's first alphabet, called proto-Sinaitic script. This script, invented by Canaanite workers at an Egyptian turquoise mine in the Sinai region, developed into the Phoenician alphabet, which later inspired the early Hebrew, Greek and Roman alphabets.

Editor's note: This article was originally published on Sept. 8, 2016 and it was updated on May 23 to include information on the genetic study and new archaeological finds.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Owen Jarus is a regular contributor to Live Science who writes about archaeology and humans' past. He has also written for The Independent (UK), The Canadian Press (CP) and The Associated Press (AP), among others. Owen has a bachelor of arts degree from the University of Toronto and a journalism degree from Ryerson University.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.